“De-Extinction” of the Dire Wolf: Unpacking the Science and Issues of Concern [By Mohammed Thajammul Hussain Manna – B.E. (Aeronautical Engineering), B.A. (Islamic Studies), currently pursuing M.S.W.; passionate advocate for animal conservation.]

The recent announcements concerning the “de-extinction” of dire wolves have ignited considerable public interest, painting a picture of these formidable predators once again gracing our landscapes. Such scientific advancements, showcasing humanity’s remarkable intellect, naturally prompt profound reflections on life, creation, and our place in the natural order.

However, a deeper examination of the scientific claims and methods employed reveals a reality far more nuanced than a simple resurrection, prompting critical discussions about the true meaning of species conservation, ethical boundaries, and the judicious allocation of resources amidst a pressing global biodiversity crisis.

The True Dire Wolf: A Distant Relative, Not a Direct Ancestor

The dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus), an extinct canine species, roamed the Americas during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene epochs, roughly 125,000 to 10,000 years ago. These creatures were notably larger and more robust than modern gray wolves (Canis lupus), characterized by a more massive skull, larger teeth, and sturdier limbs, indicative of their adaptation to preying on large megaherbivores. Fossil evidence, particularly over 3,600 specimens from the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits, confirms their widespread presence across North and South America.[1]

Crucially, recent genetic research has established that dire wolves were not direct ancestors of any living wolf species. Their lineage diverged from that of gray wolves, coyotes, and dholes nearly 5.7 million years ago, placing them closer genetically to African jackals than to gray wolves. This profound evolutionary separation meant that, despite overlapping territories for millennia, dire wolves and gray wolves could not interbreed naturally. The dire wolf’s extinction, occurring during the Quaternary extinction event approximately 10,000 to 13,000 years ago, is largely attributed to their specialized hunting adaptations, which rendered them vulnerable as their large prey vanished due to climate shifts and increased human competition[2]. Unlike the more adaptable gray wolf, the dire wolf’s specialized build hindered its ability to hunt smaller, faster prey, ultimately contributing to its demise.[3]

Decoding the De-Extinction Claims

The buzz surrounding dire wolf “de-extinction” primarily stems from initiatives by biotechnology firms such as Colossal Biosciences. In April 2025, Colossal Biosciences announced the birth of three wolf pups—named Romulus, Remus, and Khaleesi—proclaiming them the “world’s first successfully de-extincted animal[4].” The company stated that its team “took DNA from a 13,000 year old tooth and a 72,000 year old skull and made healthy dire wolf puppies.” They reported executing 20 precise genetic edits to the gray wolf genome, with 15 of these edits incorporating ancient dire wolf variants, aiming to imbue the new animals with physical traits such as a larger, stronger build, and a longer, lighter-colored coat.

Another earlier project, a different one- the “Dire Wolf Project” – started in 1988, aimed to revive the species through selective back-breeding of domestic dogs. However, this project is not based on scientific methods and explicitly states it does not breed in any modern wolf content, focusing on creating a dog breed with the appearance and temperament of the extinct dire wolf. The current discussion, however, specifically centers on Colossal Biosciences’ genetic engineering approach.

The Mechanics of “Rebirth”: Genetic Engineering and Cloning

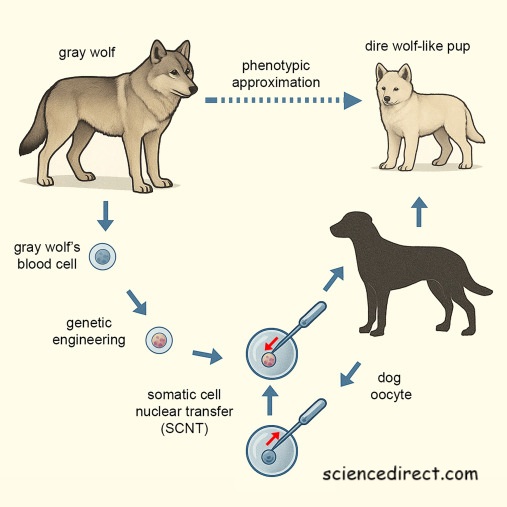

Colossal Biosciences’ methodology involved a multi-stage genetic engineering and cloning process. Initially, ancient DNA was extracted and sequenced from two dire wolf fossils—a 13,000-year-old tooth and a 72,000-year-old ear bone—to reconstruct high-quality ancient genomes.

Scientists then compared these dire wolf genomes with those of living canids, including gray wolves, to pinpoint genetic variations responsible for the dire wolf’s distinctive characteristics. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) were harvested from the blood of a gray wolf and subsequently genetically modified using advanced multiplex genome editing tools, such as CRISPR[5]. This process introduced 20 precise edits across 14 genes, incorporating 15 ancient dire wolf variants designed to mimic traits like increased size, muscle mass, and coat color.

The edited nuclei from these cells were then transferred into enucleated donor oocytes (egg cells), a technique known as somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). The resulting embryos were cultured in vitro and then implanted into domestic dog surrogates. This ultimately led to the birth of the three pups. Colossal underscores that these animals are not direct clones, as they do not possess an exact replication of the extinct dire wolf’s genetic material, but rather represent a “genetic hybrid.”

Hybrids, Not True Dire Wolves: A Matter of Genetics

Despite the ambitious rhetoric, many scientific experts contend that the animals created by Colossal Biosciences are not true dire wolves but genetically modified gray wolf hybrids. This distinction is critical and stems from the profound genetic divergence between the two species and the specific genetic manipulation techniques employed.

As previously noted, dire wolves and gray wolves are not closely related, having diverged nearly 5.7 million years ago and belonging to different genera (Aenocyon dirus vs. Canis lupus). They were incapable of natural interbreeding. Colossal Biosciences’ method involves modifying the genome of a living gray wolf to introduce dire wolf-like traits. While “extinct variants” were incorporated, “no ancient dire wolf DNA was actually spliced into the gray wolf’s genome.” Essentially, the process modifies a gray wolf to phenotypically resemble a dire wolf, rather than resurrecting the original species’ complete genetic identity. As some scientists aptly describe it, this is akin to “poking at a modern gray wolf genome to dress it up in a prehistoric costume—like gluing saber-teeth on a tiger and calling it a Smilodon.” Colossal’s chief scientist, Beth Shapiro, has herself clarified that these “dire wolves” are indeed “genetically modified gray wolves.”[6]

Hybridization and the Principles of Conservation

The creation of hybrids, while a remarkable scientific achievement, often stands in contrast to the fundamental tenets of species conservation. Conservation efforts are primarily aimed at preserving the genetic integrity and unique evolutionary pathways of distinct species. Anthropogenically[7] (human-introduced non-native) induced interspecies hybridization is generally viewed with caution by conservationists.

Introducing hybrids can blur species boundaries, potentially diluting the gene pool of existing species and introducing unpredictable ecological consequences. An animal engineered as a mix of two species, even if designed to mimic an extinct one, lacks the full genetic diversity, behavioral patterns, or complex ecological role of the original species. Ecosystems are products of millions of years of co-evolution, and a genetically altered hybrid cannot perfectly replicate this intricate balance.

A pertinent example is that of hybrid big cats like ligers (lion father + tiger mother) and tigons (tiger father + lion mother). These animals are largely human-made, as their natural ranges rarely overlap. Such hybrids often suffer from significant health issues and birth defects, with male offspring frequently being sterile. Conservation organizations widely oppose the intentional breeding of these hybrids in captivity because they do not contribute to the conservation of purebred lion or tiger populations. For instance, a liger or tigon would not be counted as a “tiger” in population figures or genetic diversity assessments for tiger conservation programs. This strict adherence to genetic purity underscores how interspecies hybridization is generally not utilized for animal conservation, particularly when focused on preserving wild populations.

In the case of the “dire wolf” hybrids, while the intent might be to reintroduce a dire wolf-like animal, the fact that it is a genetically modified gray wolf means it lacks the distinct evolutionary history and genetic makeup of the true Aenocyon dirus. It cannot be considered a restoration of the extinct species in a true conservation sense.

Beyond Science: Spectacle, Ethics, and Resources

The captivating prospect of resurrecting extinct species, especially charismatic megafauna, undeniably draws public attention. Companies like Colossal Biosciences acknowledge this appeal, envisioning de-extinction as a potential driver of public interest and ecotourism revenue. However, this “wow factor” can obscure the scientific complexities and ethical dilemmas, potentially prioritizing novelty over genuine conservation.

This phenomenon is not unprecedented. Zoos and private collections have historically showcased hybrid animals, attracting large crowds drawn to their unusual nature[8]. While generating temporary excitement, such exhibits can fundamentally misrepresent the goals of species conservation. The risk with “de-extincted” hybrids is that they become living curiosities, confined to reserves or zoos, rather than thriving, wild populations capable of fulfilling their true ecological roles. This sensationalism could inadvertently diminish the gravity of extinction, fostering a false belief that lost biodiversity can simply be “brought back” through technological means.

One of the most significant ethical criticisms against de-extinction efforts is the immense financial and intellectual investment required. Projects like the woolly mammoth de-extinction, for instance, have garnered over $150 million in funding. Critics argue that these vast resources—money, specialized scientific talent, and infrastructure—could be far more effectively deployed to combat the ongoing global biodiversity crisis by bolstering existing conservation programs. Many critically endangered species face imminent extinction due to habitat loss, climate change, and poaching. Diverting funds and attention to de-extinction projects, particularly those yielding hybrids, risks undermining these crucial, proactive efforts. As one professor noted, “without major increases in budgets, it would be like a one-step forward, two-step back scenario.”[9] These funds could instead preserve rainforests, restore coral reefs, combat poaching, or establish protected wildlife corridors—actions with demonstrable and immediate benefits for countless existing species.

Rechanneling Innovation: A Future for De-Extinction Technology?

While the current dire wolf “de-extinction” project raises concerns, the underlying genetic technologies, including advanced gene editing and cloning, hold considerable potential if applied with prudence and ethical foresight. A rigorous framework is necessary to evaluate projects, prioritizing those that offer genuine conservation benefits and minimize ecological risks.

One promising application could be the reproduction of recently extinct species where suitable habitats still exist and where a true genetic replica (or very close approximation) can be achieved. The Pyrenean ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), for example, was briefly “de-extincted” in 2003 through cloning from preserved cells, though the clone died shortly after birth due to lung deformities. Refined techniques could potentially reintroduce species whose ecological niche remains viable and whose return would not destabilize current ecosystems.

Furthermore, this technology could facilitate “genetic rescue” for critically endangered species, helping to restore lost genetic diversity or introduce beneficial traits from related lineages. Colossal’s development of non-invasive blood cloning for red wolves, alongside their dire wolf project, illustrates how these technologies could support existing conservation efforts by enhancing genetic variability in vulnerable populations.

However, stringent oversight is paramount. This must include comprehensive ecological impact assessments, evaluating the potential for resurrected species to become invasive, introduce new diseases, or their ability to adapt to contemporary environmental conditions. The focus should be on species whose absence has created a clear ecological void that their reintroduction could genuinely fill, rather than simply bringing back charismatic animals for their novelty.

Understanding Our Place: Ethical and Spiritual Reflections

Beyond the scientific and resource allocation debates, the prospect of de-extinction compels us to reflect on deeper ethical and spiritual questions. The process of extensive genetic editing and cloning often involves significant trial and error, leading to high rates of miscarriages, stillbirths, and birth defects. The welfare of surrogate mothers, particularly if they are themselves endangered species, also presents ethical challenges regarding their instrumentalization. Ensuring the well-being of these engineered animals, from conception through their lifespan, is a critical moral imperative.

Reintroducing any species into an ecosystem that has undergone profound changes over millennia is inherently unpredictable. The modern environment might not be suitable, the resurrected species might not fit its historical ecological niche, or it could even become an invasive species, disrupting the existing balance. Moreover, the exciting prospect of de-extinction could create a “moral hazard,” wherein public and political will to address current extinction threats diminishes, under the false assumption, as we stated earlier, that technology can always “bring them back” later. This could divert attention and resources from crucial, preventative conservation.

Can Science And Technology ‘Bring Back The Dead’?

The discussions surrounding “de-extinction” also touch upon a fundamental question that resonates across many faiths: humanity’s role in creation. To some, these efforts might seem like “playing with nature,” an attempt to usurp powers that belong to a Higher Power. However, a more balanced perspective suggests that such scientific endeavors, while showcasing incredible human ingenuity, operate within the boundaries set by Almighty Allah, The Creator.

Humanity, endowed with intellect and curiosity, is entrusted with the stewardship of the Earth. Our scientific advancements are a manifestation of the cognitive abilities bestowed upon us by the Creator. Yet, there remains a clear distinction between human capability and divine power.

What scientists are achieving through cloning and genetic engineering is a process of reproduction using living material, not resurrection from absolute death or the restoration of a soul to a perished body. They are using living cells to produce living beings; they are not converting a dead cell into a living one, nor are they breathing life into something that has ceased to exist entirely. This fundamental distinction underscores that while we can manipulate the building blocks of life, the ultimate act of bestowing life, truly creating from nothing, and bringing the dead back to existence rests solely with The Creator.

Almighty God, Allah, says in The Quran: “O people, an example is presented, so listen to it. Indeed, those whom you call upon besides Allah will never create [as much as] a fly, even if they gathered together for that purpose. And if the fly should snatch away from them a thing, they would not be able to get it back from him. Weak are the pursuer and [also] the pursued.” (Quran 22:73)

This verse serves as a profound reminder that even the smallest, seemingly insignificant creature like a fly is beyond human creation, let alone the recreation of a complex being from absolute nothingness or the re-establishment of a soul.

Scientists can manipulate existing living matter, assemble complex organic molecules, or even guide the development of an embryo from a living cell, but they cannot imbue a lifeless form with a soul or truly bring back a departed spirit.

Islam has always encouraged the pursuit of knowledge and scientific inquiry. The Quran is filled with verses that urge contemplation of the natural world, seeing it as signs (Ayaat) of Allah’s magnificent creation. Science, when pursued with a clear understanding of its boundaries, is a means to better appreciate the intricacies of Allah’s handiwork and the vastness of His wisdom. It does not, and cannot, contend with The Almighty God, Allah. Instead, it serves to unveil the wonders of His creation, reinforcing, for the believer, the majesty of the Creator.

Therefore, we must view these scientific achievements not as a challenge to Allah’s sovereignty, but as a demonstration of the intellect He has granted us. The power to truly create, to resurrect, and to determine life and death remains exclusively with Him. These ‘de-extinction’ attempts are merely human efforts to replicate certain physical forms using existing biological templates, which, while impressive, fall infinitely short of the divine act of creation and resurrection.

Quick Summary

The buzz about ‘de-extinction of dire wolves’ is captivating, but the science needs a closer look. What’s being presented isn’t a true resurrection of the ancient dire wolf, but a complex act of genetic engineering. Dire wolves (Aenocyon dirus) were distinct from gray wolves (Canis lupus), diverging nearly 5.7 million years ago. They couldn’t interbreed naturally & went extinct ~10k years ago. Their lineage is unique, not a direct ancestor of modern wolves. The ‘new dire wolves’ from Colossal Biosciences are genetically modified gray wolf hybrids. Scientists edited gray wolf DNA to mimic dire wolf traits, not bringing back the original species. It’s an engineered proxy, not Aenocyon dirus. Creating hybrids isn’t species conservation. Real conservation preserves genetic integrity & unique evolutionary lineages. Spending vast resources on hybrids can distract from urgent needs of existing endangered species, like ligers vs. wild tigers. This raises profound questions: Are we creating spectacles or truly restoring ecosystems? From a Muslim’s perspective, true life-giving & resurrection are divine prerogatives. Human science manipulates living matter, it doesn’t create life from absolute death. Ultimately, our precious resources are better spent preventing current extinctions and preserving the magnificent biodiversity we still have. That is where true conservation and genuine impact remain.

[1] See more here- https://www.sdnhm.org/exhibitions/fossil-mysteries/fossil-field-guide-a-z/dire-wolf/

[2] Summarized from- https://direwolfproject.com/

[3] Read more- https://www.arcticfocus.org/stories/dire-wolves-went-extinct-13000-years-ago-thanks-new-genetic-analysis-their-true-story-can-now-be-told/

[4] De-extincted: That is- brought back from extinction.

[5] CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) is a revolutionary gene-editing tool derived from a bacterial defense system. It enables precise modifications to DNA sequences using a guide RNA to target specific genome regions, holding promise for treating genetic diseases and improving crop yields. CRISPR-Cas9 enables precise DNA editing by using a guide RNA to target specific sequences. [For DNA altering: The Cas9 enzyme cuts the DNA, allowing researchers to introduce changes. This technology has potential applications in treating genetic diseases, improving crop yields, and developing gene therapies with unprecedented precision and efficiency.]

[6] See- https://www.livescience.com/animals/extinct-species/our-animals-are-gray-wolves-colossal-didnt-de-extinct-dire-wolves-chief-scientist-clarifies

[7] Anthropogenically introduced species are non-native species introduced to a new environment by human activity. This can occur intentionally, such as for agriculture or hunting, or accidentally through trade or travel. These species can outcompete native species, alter ecosystems, and cause economic and environmental harm, potentially disrupting the native biodiversity and ecosystem balance.

[8] Read about the Tigons and Li-Tigons of the Alipore Zoo (Kolkata, India). [https://www.downtoearth.org.in/wildlife-biodiversity/the-forgotten-tigons-and-litigons-of-alipore-zoo-and-other-hybrids-78775]

[9] “There would be sacrifices,” said study author Joseph Bennett, a professor of biology at Carleton University in Ontario. “Without major increases in budgets, it would be like a one-step forward, two-step back scenario.” [https://www.livescience.com/58027-cost-of-reviving-extinct-species.html]